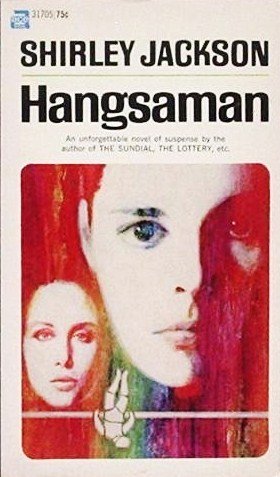

Shirley Jackson’s 1951 novel Hangsaman occupies an odd position in her substantial repertoire of novels and short

stories. On the surface, the novel functions similar to a typical all-American

bildungsroman, focusing on the interior life of a 17-year-old girl, Natalie

Waite, as she leaves home, her domineering father, emotionally vacant mother,

and her childhood, behind, and begins her studies at a small women’s college.

This surface plot quickly reveals itself to be a sort of narrative red herring:

uncanniness bleeds into the water and suddenly the reader is shoved overboard

into the deep end, something far more complex and even sinister occurring under

the guise of a standard coming-of-age story. Hangsaman is arguably the

most experimental and inchoate of Jackson’s work, and thus, frustrating for

many of its readers. The novel is perhaps Jackson’s least-discussed work, only

seriously considered by a handful of scholars thus far, and this relative

absence of criticism may draw directly from the text’s narrative strangeness:

unlike, say, the archetypal Gothic-phantasmic vision of The Haunting of Hill

House, or the succinct, unsettling-but-clear allegory of “The Lottery,” Hangsaman is far more difficult to accurately classify or pin down.

![]()